Inspiring Older Readers

posted on 20 Feb 2016

posted on 20 Feb 2016

Barry Hines

Barry Hines’ second novel A Kestrel for a Knave – filmed in 1969 by Ken Loach as Kes and subsequently reissued by Penguin under that same title – went on to become a set book in schools and in the past forty years has never been out of print. Hines wrote the screenplay and the book has also been adapted for stage.

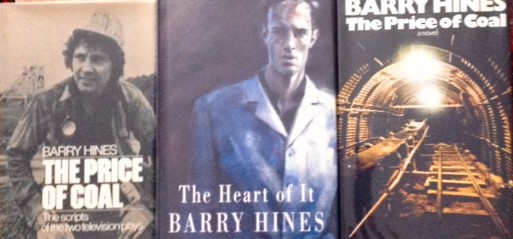

To many Hines became a working class hero – narrowly avoiding a working life spent underground in the local pit and instead becoming a professional novelist and screenwriter, close collaborator of Ken Loach, and author of classic and highly influential dramas such as The Price of Coal, and the controversial Threads, which depicted a nuclear strike on Sheffield.

I haven’t read Kes since 1974 – at least that is the date inside my 25p Penguin film tie-in copy – but I did so just the other day and it was a remarkable experience. The world Kes depicts – white, working class, northern, industrial – has vanished, along with the mines and pit villages that were central to it. The grinding inequality, class discrimination and poverty that inform Hines’ writing haven’t disappeared, of course. “There are still Billy Caspers,” Hines has said.

Kes the novel is not without its flaws. For such a short book it sometimes doesn’t move forward at quite the pace that is needed. At some crucial points descriptive set-pieces interrupt the narrative without (in my view) heightening the drama. Nonetheless it deserves its place amongst classic working class novels – but it also deserves a place alongside TH White’s The Goshawk, JA Baker’s visionary The Peregrine, and the more recent prize-winning H is for Hawk by Helen Macdonald, for the kestrel that lies at the heart of Hines’ novel is in its own way as enduring a character as young Billy Casper.

Kes made me move straight on and reread what I think must be Hines’ masterpiece, The Gamekeeper, his fourth novel, published in hardback in 1975 and in paperback, again by Penguin, in 1979. (There was an intervening third novel, First Signs, published in 1972 which I have never even seen a copy of.)

The Gamekeeper, also filmed with Loach in 1980, is an almost documentary-novel. It covers a year in the life of George Purse, a former steel worker now gamekeeper, employed on a minor aristocrat’s estate in the north of England. Purse’s job is to rear and safeguard the pheasants that the Duke and his guests shoot in the woods and coverts during the shooting season. The lived texture and minutiae of rural working class life have an almost hallucinatory intensity. Although separated by only six or seven years from Kes, the writing is of an entirely different order – subtle, nuanced, exacting, observant, more literary. Purse prepares for his day’s work by banging the mud from his boots and it falls from their tread “like typeset from a tray”. A ferret has slender claws with a shallow curve, “the shape of a foil when it touches its mark”. While markedly more mature, Hines’ prose has lost none of its steely gaze or muscularity.

The Gamekeeper is a book of great beauty, but if it were only this then it wouldn’t be the success that it is; and nor, I suspect, would Hines himself have regarded it as succeeding on the terms he set for it, for The Gamekeeper is not, he has said, a book about gamekeepers, it is a book about class. And class consciousness – and class anger and class compromise and class betrayal – are as tightly woven into its fabric as the details of daily rural life are into its scrupulous observation. It is a huge achievement.

There is relatively little written about Hines’ work and not everything is currently in print. Penguin should reissue all of his novels in handsome new editions (as they did A Kestrel for a Knave), with splendid jackets and new introductions. It would be a fitting tribute. Hines is now 76 and has Alzheimer’s disease and lives in long-term care. Although only diagnosed in 2008 his condition has deteriorated rapidly. He was able to take part in interviews with journalists marking the fortieth anniversary of the publication of Kes, but gave what he said was his “last ever” interview in On, the Yorkshire magazine, in November 2011.

Alun Severn

February 2016