Inspiring Older Readers

posted on 08 Nov 2015

posted on 08 Nov 2015

Mr Norris Changes Trains by Christopher Isherwood

Published in 1935, Mr Norris Changes Trains, is the first part of what would become the Berlin Stories and they in turn would provide the source material for the film and stage play Cabaret. Later in life Isherwood would renounce this book as too frivolous and light-weight to do justice to the time it was written in and that the rise of the Nazi Party was not an appropriate backdrop for what is essentially (and these are my words) a plot line that would not be out of place in an Ealing comedy.

However, I think this judgement is rather harsh and that there is plenty here to reward a modern day reader. William Bradshaw – a thinly disguised self portrait of Isherwood himself – is a young, gay, British adventurer seeking to experience the decadence and liberality of Weimar Germany by living frugally in Berlin, supporting himself by teaching and translating. On the train from Holland into Germany he meets another Briton, Arthur Norris, who he finds physically unpleasant but oddly fascinating and intriguing. Norris is an exaggerated fop who wears wigs, pomanders himself excessively and lives well beyond his means and, as his friendship with Bradshaw grows, we begin to see he is almost certainly an amoral crook involved in any number of multi-layered and almost certainly dangerous business and personal activities.

Naively, Bradshaw allows himself to be drawn into Norris’s web and soon becomes unable to untangle fact from fiction when it comes to his new friend. Although Norris appears to always be only one step ahead of ruin – financial and reputational – he seems to be able to exercise an extraordinary charm over those he comes into contact with. However, it soon becomes clear he is involved politically in what is happening in Berlin as much as he is involved financially and it he reveals to Bradshaw that he has thrown in his lot with the Communist Party that is the chief opposition to the rise of Hitler.

Ultimately, nothing Norris tells Bradshaw or us as readers can be trusted. We eventually discover that Norris has been acting as a double agent – passing information and intelligence about the Communists for money to contacts in Paris who support the rising Nazi regime. Under threat that his political and sexual secrets will be revealed by his former secretary, Schmidt , he decides the only way to end the blackmail is to flee Germany – which he does as the Nazis arrest and murder the leaders of the Communist Party. The book ends with Bradshaw getting letters from Norris that chronicle him moving from one country to another constantly tracked and trailed by his nemesis, Schmidt.

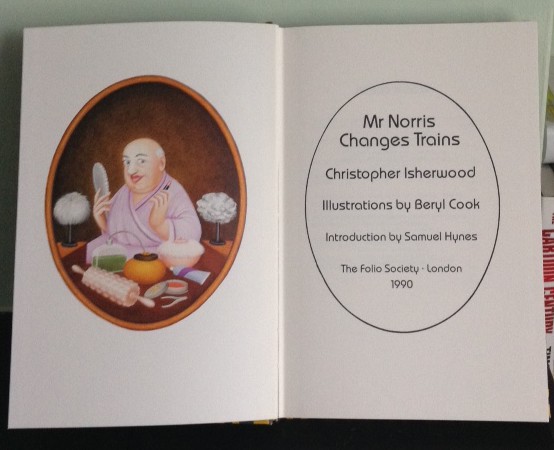

One of the most difficult aspects of the book is that the farcical elements of this story require the reader to suspend some critical judgement – Bradshaw surely could never have been so stupid and blind to Norris’ duplicity and why on earth would he be so fascinated by this rather repellent creature in the first place? But, if you can overcome these issues, Isherwood’s ability to carry the story along has some delightfully drawn moments. The descriptions of some of the more excruciating social set pieces are finely drawn and whilst the politics is underplayed, we now know enough to pick up and fill in the darker aspects of the story that the author failed to emphasise at the time. The triumph of the book however is the monster that is Norris – he positively leaps off the page in all his three dimensional glory. The copy I have is a Folio edition that has been illustrated by Beryl Cook who depicts him – fittingly I think - in her trade-mark style, emphasising his corpulence and fleshiness.

Ultimately it is the character of Norris that makes or breaks the book – you won’t love him I suspect but you will find that Isherwood has made him revoltingly fascinating.

Terry Potter

November 2015