Inspiring Older Readers

posted on 09 Sep 2015

posted on 09 Sep 2015

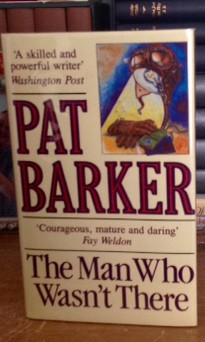

The Man Who Wasn’t There by Pat Barker

This is a slim, even cryptic novel of life in post-war, black and white Britain. 12 year old Colin has no father at home but we are never really sure why. His mother, Viv, tells him that died in the war but we know early on that this is probably untrue. We get hints that he never came back from the war because of possible criminal activities but neither we, nor Colin, ever get the definitive answer. Anyway, Viv – a sparkling floosy of a character - is too busy to spend time with her son because she works unsocial hours as a waitress in a club and is trying to rebuild her own love life. Colin’s time is spent surrounded by working class women and he is struggling to understand his own emotions as a boy on the verge of puberty without a male role model.

To help him survive the everyday ordinariness of his existence in an anonymous northern town Colin fantasises and dramatizes his life, intercutting reality with a running drama of the French Resistance featuring himself and the cast of characters he spends his time with. Always in the background (seemingly literally at times as a spectral character in black) is the man who is not there.

Barker has created a story dramatizing the trauma of growing up and identity crisis that must have been common shortly after the war when husbands and fathers failed to come home - for whatever reason. How does a young boy struggle to become a man in these situations and, in any case, what does being a man mean?

Barker is incapable of writing anything other than intelligent and thought-provoking novels but I found this relatively early book a bit too schematic and slightly irritatingly enigmatic – there are just too many dangling ends and gaps left for the reader to fill.

Clearly Barker has her literary influences. There are strong echoes here of novels that must have been in Barker’s mind as she was writing – Keith Waterhouse’s Billy Liar and, particularly, Kes by Barry Hines. Colin’s time at school and the bullying of the fat boy in the Games lesson have Billy Casper’s schooldays written all over them.

There are, of course, no definitive endings for stories like the one Barker tells and so the fact that the novel ends ambiguously is entirely appropriate. However, that doesn’t necessarily make it a satisfactory ending and I personally felt I’d been allowed entry into Colin’s world and then dragged from it in an untimely way without being given quite enough information to draw my own conclusions.

Terry Potter

September 2015